How to Get Rid of Voice Breaks in Singing

Voice breaks can be explained by understanding the somewhat complex topic of formants.

How does an understanding of formants and harmonics affect our singing? Why would we as singers care about all this complicated stuff? The answer is that when you understand formant tuning, (traditionally known as “resonance”) you can get a much bigger bang for your singing buck!

When the formant frequency of the sung vowel is near the frequency of a harmonic, there is an increase in power without an increase in air pressure. In other words, you can get a much stronger and more resonant vocal sound without pushing the voice.

Formant tuning also helps us transition through the first bridge or primo passaggio– the place where everything tends to fall apart. This transitional area is where most untrained singers tend to pull the chest voice too high, creating strain and voice breaks.

When singers learn to modify vowels, they can transition through these tricky areas with a consistent and even vocal sound rather than the yodel effect of two entirely different voices.

Understanding the slight adjustments needed to transition through all the bridges beyond the primo passaggio can help singers achieve a greatly extended range. The voice is more consistent, reliable, and beautiful. Voice breaks and cracking are eliminated.

Developing a connected and smooth transition through the first bridge or primo passaggio is of primary importance to singers and teachers. One of the causes of registration changes or the turn over of the voice is the interaction of the first formant of the sung vowel and the harmonics (particularly the second harmonic) of the rising pitch.

FORMANT HANDOFF

When we sing low pitches, there are more harmonic frequencies near or under F1.

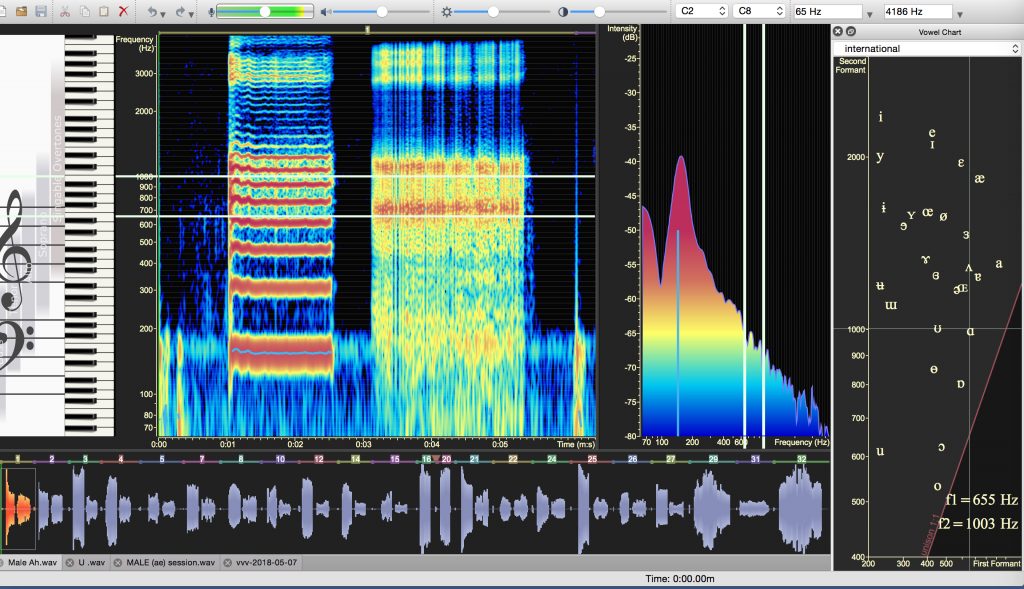

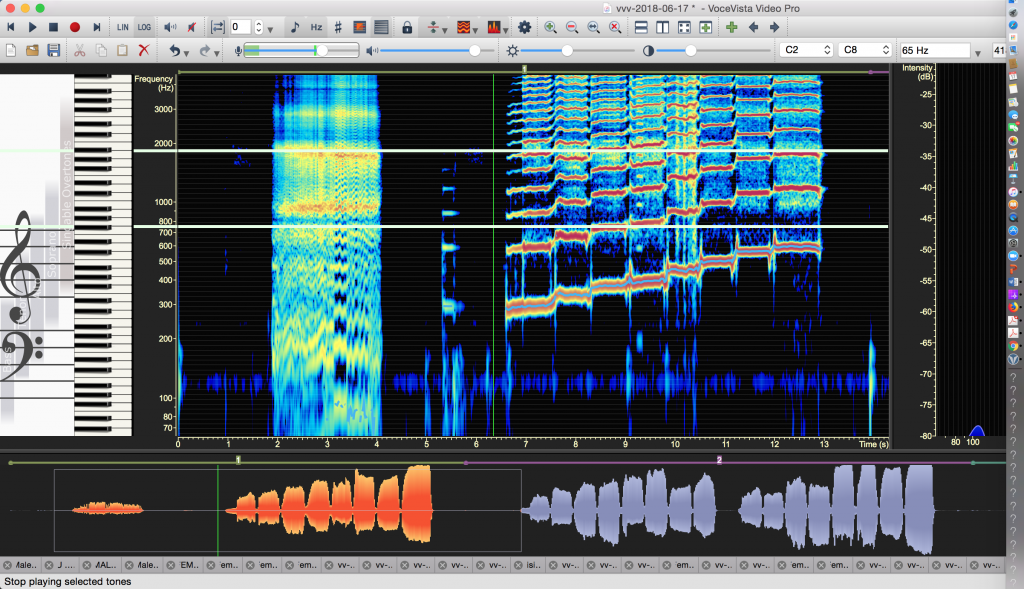

Male [a] on Eb3

Singing from low to high is challenging for most singers. Here is the acoustic perspective on why this is so:

The second harmonic is an octave above the fundamental or sung pitch, which is also called F0 or H1. When the frequency of the second harmonic (the octave above the pitch) becomes higher than the first formant vowel frequency as the pitch rises, the voice naturally wants to “turn over” or change registers.

When we sing an ascending scale, the harmonics (which are fixed) rise along with the fundamental F0 or H1. Along with all the harmonics, the second harmonic (one octave above the pitch) continues to go up as we sing progressively higher notes.

Eventually, the frequency of that second harmonic is going to be higher than the frequency of the first formant of the vowel being sung.

This is known as crossing. The harmonic frequency has crossed, or gotten higher than, the first formant frequency of the sung vowel.

When the second harmonic crosses over the first formant, F1, vocal fold vibration is destabilized. We are now in yell mode and likely to experience a voice break if we continue to sing higher and higher with this approach.

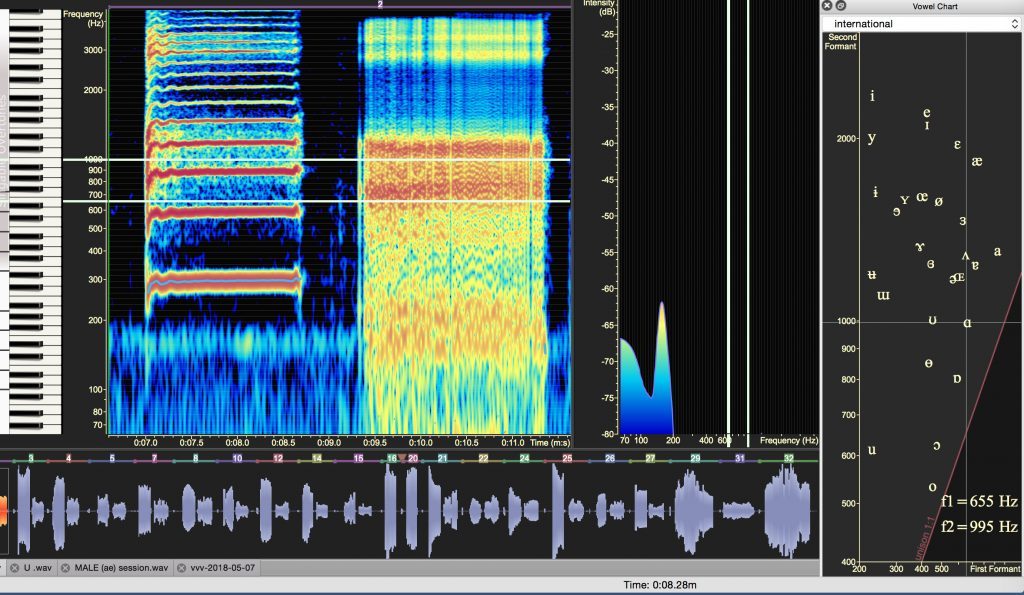

Here you can see how our female singer tracked the rising second harmonic by increasing F1 frequencies by lifting the larynx, making the pharyngeal resonator smaller.

Female Tracking H2 with F1

![]()

When the second harmonic (the octave above the pitch) approaches the peak of the first formant, we get the F1/H2 coupling- the yell timbre.

Female Yell Mode [ɑ]

This F1/H2 coupling can cause problems, however, if taken too high in pitch. If we hold on to the F1/H2 coupling as the pitch ascends, we are tracking the second harmonic, which is rising as pitch ascends, with the first formant.

Singers who belt artificially raise F1 to try to stay in the chest voice longer as pitch ascends.

This is often accomplished by increasingly opening the vowel to raise F1 to track the rising second harmonic. To pull chest, or belt higher than you should, the vowel has to be open.

That is why you hear rock singers pronouncing words like Valerie as Valer-ay– they are trying to avoid the more closed [i] vowel- or changing the vowel from an [u] to an [æ] for example-singing [æ] l[æ]v y[æ]w instead of I love you.

F1/H2 is appropriate for the pitches under the primo passaggio; it becomes problematic, however on pitches in and above the primo passaggio.

Female Yell Mode

FORMANT/VOWEL TUNING

What is needed is a different resonance strategy- that of the mix. When we mix, F1 hands off to F2, the second formant. A smooth transition through the primo passaggio requires a handoff from F1 resonating the second harmonic (chest voice) to F2 resonating the third or fourth (and higher) harmonics (mix voice).

This strategy is for contemporary singing; a classical soprano uses a different resonance strategy.

To avoid vocal fold instability (flipping, cracks, and breaks), the frequency of the formant generated in a resonator should not be higher than the harmonic it is resonating.

Whenever there is a crossover (a formant frequency becomes higher than the harmonic, OR the harmonic becomes higher than the formant), the potential for breaks, flips, and vocal cracks are present.

Formant tuning is adjusting the formant frequency of a sung vowel to be closer to a specific harmonic frequency in the vicinity of the vowel formant, thereby increasing the acoustic energy of the harmonic.

Formant or vowel tuning can increase vocal fold adduction, closed quotient, and inertive reactance, increasing feedback energy in the vocal tract. This means singing becomes efficient, powerful, beautiful, and easy.

Singers adjust or tune vowels as the pitches rise to keep the vocal tract aligned with the rising harmonic to avoid instability and to transition to a second formant dominant resonance strategy.

For the contemporary mix singer, when F1, which is resonating the second harmonic, (H2) reaches the pitch area of the natural primo passaggio or first bridge, then F2 should take over, resonating the third (H3), fourth (H4) and higher harmonics.

This is the formant hand-off or transition that should occur at the first bridge.

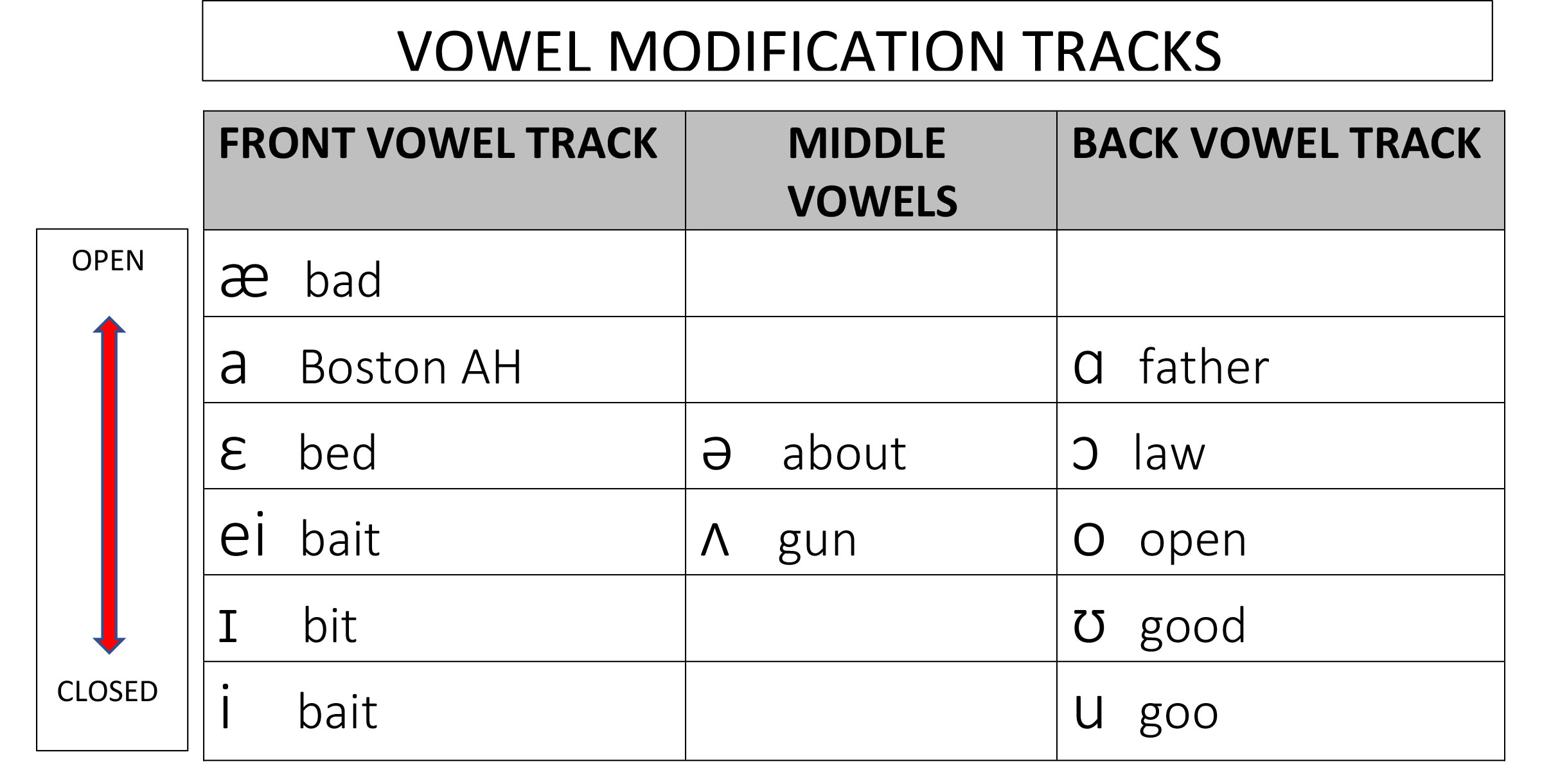

VOWEL MODIFICATION TRACKS

This hand-off only happens, however, if the vowel being sung encourages this transition. Good vowel tuning creates an even, consistent tone with no breaks or sudden changes in timbre throughout several octaves. This is the sound of the contemporary mix singer.

One vowel tuning method is to center or shade vowels by bringing them closer to [ʌ] (UH) or [ʊ] (as in book) to transition through the primo passaggio. If needed, an entirely different vowel may be substituted- usually the next closest vowel on the vowel chart.

There are two vowel tracks- the front track and the back track. Front vowels substitute for other front vowels and back vowels substitute for other back vowels.

The singer alters formant frequencies by modifying the vowel- changing the size or shape of the resonator by altering the position of the articulators- primarily the tongue, and secondarily the lips, jaw space, and soft palate.

Moving an articulator slightly shades the vowel but preserves its essential quality. Moving the articulators changes the vowel. Vowel modification can be either of these- shading a vowel or substituting a new and more efficient vowel.

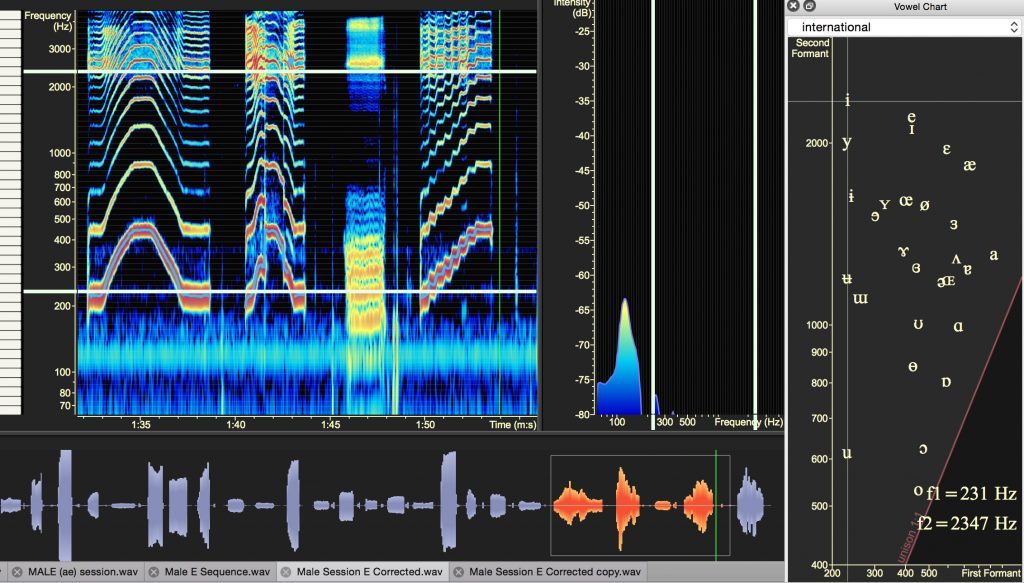

F1 plays an important role in acoustic registration as it couples or uncouples from various harmonics.

When the second harmonic frequency, H2, becomes higher than the first formant frequency, F1, the harmonic is crossing the formant. This is, acoustically, where the first register transition happens.

Because F1 frequency increases when vowels move from closed to open, this is not a specific pitch; it varies dependent upon the vowel. This acoustic registration shift is usually tied to a laryngeal registration shift- a decrease in TA activity as pitches get higher.

Vowel choice affects vocal fold function.

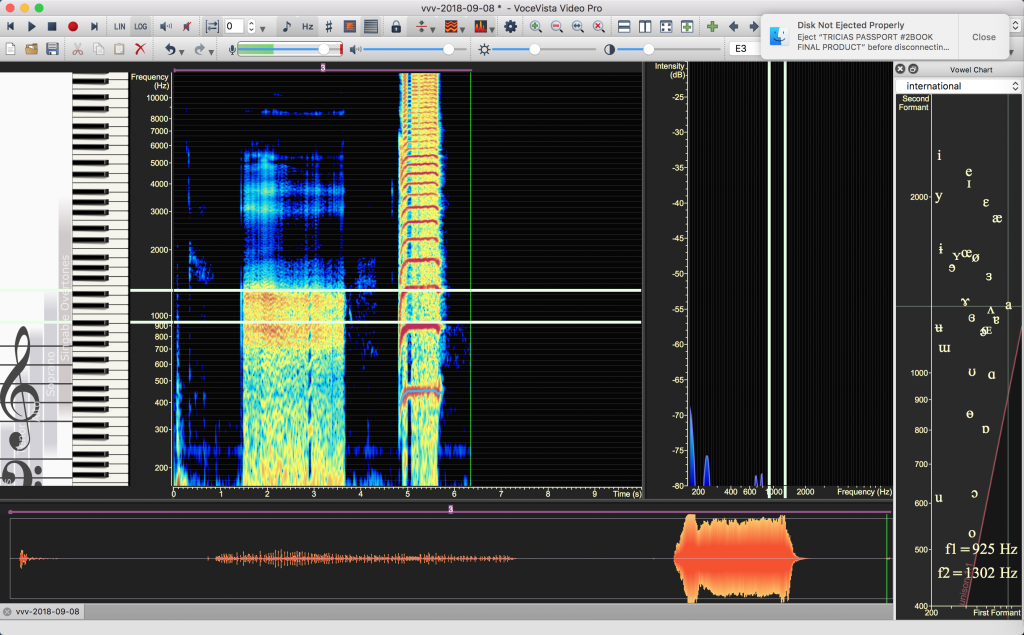

Male Primo Passaggio [i]

A stable vocal tract shape makes this transition more stable; allowing the larynx to rise in the primo passaggio can destabilize the transition, making flips and breaks more likely.

The contemporary singer will, after the primo passaggio, begin to resonate higher harmonics (H3, H4, and higher) by aligning the second formant with those harmonics.

Female [æ] Vowel Ascending Scale

When we sing pitches below the primo passaggio we don’t need to tune the vowels- we simply sing the vowel as written. That’s because there are lots of harmonics available and they are close together. We always need to have at least one harmonic in the vicinity of F1 or the sound will be thin.

Male Approach to Primo Passaggio [ɑ]

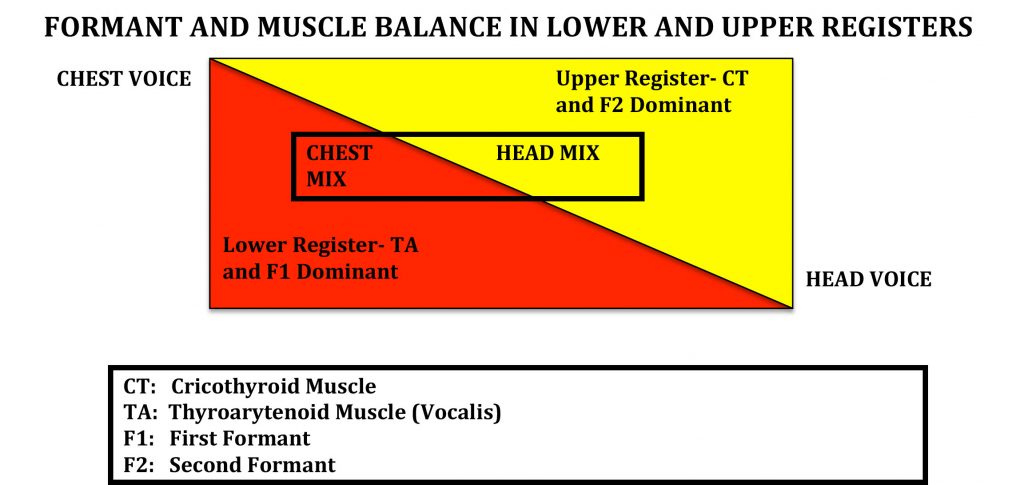

MUSCLE HANDOFF

Most singers and teachers of singing would agree that one of the greatest challenges in teaching singing is creating an even and unbroken vocal line from the lowest to the highest notes of the range without abrupt changes in vocal quality in the troublesome overlap octave- the area in which singers can produce sounds with either a mode 1, TA-dominant or mode 2, CT-dominant- phonation.

This is due not only to resonance (formant/harmonic interactions), but to interactions between certain muscles.

In the lower register (and in the speaking voice), TA muscle contraction bulges out the bottom of the fold’s inner edge. This means the vibrational wave pattern begins at the bottom of the depth of the fold and the folds spend more time together (higher closed quotient).

Greater subglottic air pressure builds in the longer closed phase of the vibrational cycle, producing stronger harmonics and richer timbre.

As pitch ascends, TA muscle activity gradually decreases. In the upper register, the balance of muscular dominance shifts to the CT (cricothyroid) muscles, with the ligament taking over much of the vocal responsibility on the highest pitches.

There is less vertical movement in the vibrational wave (this is called amplitude), less of the fold is in vibration (less vibrating mass), and fewer high-frequency harmonics are generated.

Pitch changes in the upper register are controlled by CT muscle activity. As the thyroid cartilage tilts forward due to CT muscle contraction, the vocal folds lengthen and become tauter to produce higher pitches.

The vocal folds, instead of meeting at the bottom of the depth of the fold, now meet higher on the depth of the fold.

Most untrained singers who "push chest" do so because they don’t intuitively know how to allow the vocal fold lengthening process. This skill must be developed through training with the right vocal technique.

Many untrained singers hold on to mode 1 TA-dominant phonation because this is the way we produce the speaking voice. It feels strange to us to let go of something that seems so natural.

Singing higher pitches correctly requires that the folds become longer, with less vibrating mass. If singers attempt to maintain a static vocal fold condition (shorter, thicker vocal folds) instead of allowing the folds to lengthen and thin, trouble begins!

One of the issues with this approach is that excessive air pressure must be employed to change pitch because the CT muscles are not able to do their job.

High breath pressure is potentially damaging to the folds.

To transition smoothly from the lower register to the upper register there must be a hand-off from TA-dominant to CT-dominant muscle/ligament activity. This transition is achieved with correct vowel choices, appropriate breath pressure, and consistent vocal fold compression.

A singer who mixes well gradually introduces more cricothyroid (CT) activity, decreasing TA activity as the pitch ascends. This produces a smooth register transition with no voice breaks, cracking, flipping, abrupt changes in vocal quality, or noticeable differences in registration.

Mixing requires a balance of TA (thyroarytenoid) and CT (cricothyroid) muscle activity. There is a sharing of the workload between the TA and CT muscles, with CT dominating more and more as the pitch ascends. On the highest pitches in the range, the TA muscle is no longer active, and the ligament assumes much of the tension-bearing load.

TA muscle involvement is greatest on the lowest pitches in the scale; however, as the pitch ascends the CT muscle contracts and offers resistance to the TA muscle. The degree and extent to which the TA/ vocalis muscle is activated in the upper register mix determine the timbre and strength of the sound, creating either a more robust or lighter quality mix.

Singers must learn to accept a change in resonance strategy and muscle activity as pitch ascends to avoid vocal instability. Flips, cracks, and breaks will continue to occur until the hand-off from the first formant to the second formant, and the hand-off from TA-dominant short folds to CT-dominant long folds is achieved.

If you would like to learn more about your voice AND learn to sing from home for less than you probably spend for lattes every month, check out our amazing YOU can Sing Like a Star online subscription courses for singers and voice teachers.

You can learn to sing with a self-study method- IF it's the right method. The ONLY method that can take you from beginner to professional is the YOU can Sing Like a Star online subscription course with over 600 recorded exercises.

This is the best method available and the ONLY method that takes you all the way from beginner to professional singer- for far less than the cost of in-person voice lessons!

Check this amazing course out at YOU can Sing Like a Star online subscription course.

If you are a voice teacher who wants to up your game, check out the YOU can be a Successful Voice Teacher online subscription course

With over 600 recorded exercises, including Riffs and Runs- Style, you don't need to be a great pianist or vocal stylist to be a great teacher!