How to Sing Better: Register Connection

Everyone is born with two registers- a lower register (used for our speaking voice and low notes) and an upper register (used for high notes).

One of the challenges in singing is transition between these two registers.

In the octave between approximately C4 and C5, pitches can be sung by both male and female singers using various permutations of TA-dominant lower register (modal register- short, thick folds) and CT-dominant upper register (longer/thinner folds) phonation. This area is known as the overlap octave. The problem with the overlap octave is there are so many ways to sing incorrectly in it!

We can pull chest, flip, or bring the upper register too low, to name just a few.

All these incorrect methods of producing sound have one thing in common: they are not balanced. In vocal training, particularly in the overlap octave, balance is essential. The overlap octave contains the trickiest area singers must learn to maneuver through- the challenging primo passaggio or first bridge.

BRIDGES (PASSAGGI)

The passaggio (singular) or passaggi (plural), also known as the bridge(s), are areas of transition created by muscular and resonance changes that occur when we sing ascending or descending pitches. These changes can be compared to the idea of shifting gears in a car.

Using the car analogy, one could ask, How do you know when it’s time to shift to the next higher gear when driving? The answer is obvious; when the engine starts to labor, and the RPM’s are too high, it is time to shift!

In the same way, as we sing an ascending scale, when we begin to notice unnecessary tension it is time to shift something about the way we are producing the sound.

This shifting process is a re-setting of muscle and resonance activity, occurring at specific areas of the voice and is known as bridging. The development of a smooth transition through the primo passaggio, a reinforced upper register mix, and balance between the lower and upper registers is the singer’s greatest challenge.

THE FIRST BRIDGE (PRIMO PASSAGGIO)

Passaggi or bridges are relatively predictable, occurring at approximately a tritone (augmented fourth interval) to a perfect fifth apart. The most dramatic is the first bridge or primo passaggio, the least stable section of the voice.

This area presents a significant challenge to any singer because, in this first transition, the vocal folds are changing from a shorter and thicker TA muscle dominant to a longer and thinner CT muscle/ligament dominant phonation. It is also the area where F1 activity decreases in favor of F2.

This is the area where the second harmonic, H2, crosses the frequency of the first formant, F1. The primo passaggio is the area of greatest destabilization for singers.

The transition from TA-dominant to CT-dominant phonation requires skillful coordination. It takes time, focus, and practice to achieve a smooth transition, a strong upper register, and the ability to sing an even line from low to high pitches.

In the first bridge or primo passaggio area, many contemporary singers tend to hold on to modal or lower register TA-dominant phonation too long when singing ascending pitches. This creates vocal strain as singers attempt to maintain the shorter and thicker vocal folds and F1/H2 resonance strategy of the lower register.

F1/H2 tuning and short/thick vocal folds create the “yell” quality if carried above the first bridge. Eventually, there will be a significant break in the register as the voice flips into a breathy falsetto after straining to reach pitches beyond the natural transition point of the primo passaggio.

Smooth transitioning upward through the first bridge requires a blending of upper and lower registers where, for a time, TA and CT muscles are both activated; as pitch ascends there must be a gradual decrease in TA activity and an increase in CT activity.

In the bridge- the transitional area between the lower and upper registers- singers must shift gears, so to speak, from a TA muscle dominant to a CT muscle/ligament dominant phonation to allow the folds to adjust from thick and short to longer, thinner, and tauter.

A smooth transition through the primo passaggio also requires a resonance shift; the singer must shape the resonators of the pharynx and mouth to facilitate the gradual shift of formant dominance from F1 to F2.

This is accomplished with formant or vowel tuning- modifying vowels to adjust formant frequencies, so they more closely align with a nearby harmonic, to create a boost in efficiency.

Most of us are comfortable singing in the lower register- until we decide to move higher in pitch. We eventually hit the ceiling, where it feels like no matter how hard we push, the voice simply cannot reach those high notes! And yet we hear singers every day who can hit those top notes.

Many of us wonder: Is this simply due to talent, or is there a better explanation?

Luckily, vocal science has the answer!

In the lower register, the squared shape of the vocal folds means they meet at the bottom of the fold, creating a strong H2 (second harmonic, an octave above the sung pitch).

Vowels sung below the first bridge or primo passaggio will have a first formant frequency that is higher than the second harmonic, an octave above the pitch. In this area, the first formant reinforces the second harmonic- F1/H2. This is the “chest voice,” which is more accurately called modal or lower register phonation.

As we sing ascending pitches, when the frequency of the second harmonic approaches the frequency of the first formant, the singer has reached the primo passaggio or first bridge where the voice naturally wants to “turn over”.

This is the natural transition point, based on the sung vowel, where we shift gears, a re-setting of resonance and muscle activity.

The correct strategy, if we want to transition smoothly and not yell and then flip, is to mix- that is, acoustically speaking, to allow a second formant dominance in this area (the second formant boosts the 3rd, 4th, and higher harmonics).

Additionally, the vocal folds must lengthen and TA activity must decrease. We must maintain even vocal fold compression and refrain from increasing air pressure as we sing higher.

We call this connected release- allowing the hand-off from TA-dominant to CT-dominant phonation, along with the hand-off from F1 dominant to F2 dominant resonance, by releasing just enough and not too much as we transition through the primo passaggio.

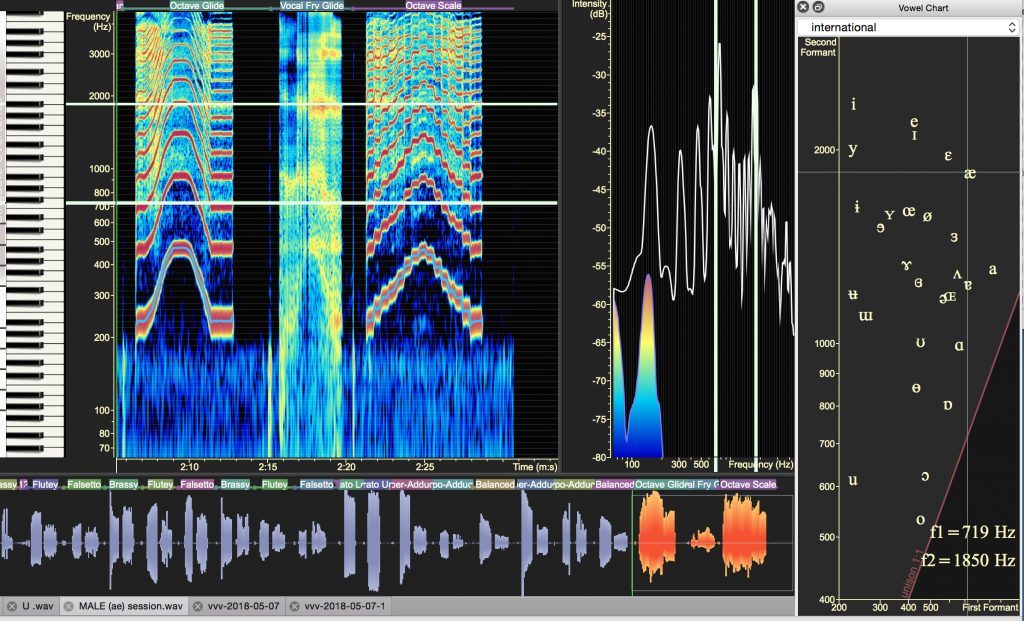

Male Primo Passaggio [æ] Vowel

The vowel, volume, musical style, and singer’s vocal development all affect the bridging process. The more open the sung vowel is, (ie the flatter the tongue is, by virtue of the vowel) the later the natural transition will occur due to higher F1 in open vowels.

Open vowels have higher first formants and tend to encourage a higher transition; closed vowels have lower first formants and tend to encourage a lower transition.

Since open vowels have a higher first formant, singers naturally bridge higher on the open vowels, like [ɑ] and [æ] than on the closed vowels, like [u].

Transitioning is also dependent upon the size of the singer’s resonator tube or vocal tract.

TA muscle activity is another factor: when we begin to enter the upper notes of the chest voice, it’s time to begin to decrease TA activity to ensure a smooth transition.

Attention should be paid to the direction of the melody: if the melody is ascending from a low to a high pitch, the singer should lighten out the voice on the notes leading up to the first bridge by using less volume and air pressure to make the transition easier. Vowel shading or substitution of a more closed vowel may also be necessary for these approach notes to the first bridge.

Contemporary female singers generally experience the first bridge at around Ab4-Bb4; the classical female singer’s first bridge is D4- Eb4. Most contemporary male singers begin the bridging process around D4-Eb4. Male operatic tenors bridge in about the same area as contemporary male singers. Baritones and basses transition sooner: Bb3 (baritones) and A3 (basses).

OTHER BRIDGES

Although less dramatic than the first bridge, the second and successive bridges can be troublesome to the singer.

Successive bridges tend to occur at about a tritone to a fifth apart. In males, the second bridge typically occurs where the females’ first bridge occurs (around Ab4), and the third male bridge begins about where the female second bridge happens (around Eb5).

Males usually have three or four bridges; female singers who employ the whistle register can have six bridges.

Women have more bridges than men do because a more substantial portion of the female voice is above the first bridge. The contemporary female second bridge begins around D5-Eb5, the third bridge begins around Ab5, and the fourth bridge begins around D6-Eb6.

Sopranos, when singing extremely high pitches, may have to allow laryngeal raising and may have few vowel choices. That’s why you usually don’t get clearly defined words on the highest pitches of the soprano voice.

On lower pitches, where harmonics are closer together, it’s easier to perceive which harmonics are being boosted or amplified, and therefore which vowel is being sung.

But on higher pitches, where harmonics are fewer and more spread out, it’s harder to hit the target, so vowels become unidentifiable. A very specific combination of F1 and F2 is needed to produce a vowel.

At high pitches, all vowels sound similar because the normal frequency range for the first formant is 250-850 Hz. Above 880 Hz (A5) the tone becomes strident and strained if the soprano tries to sing any vowel other than[ɑ] or [ʌ] (UH).

Pavarotti said pick your best vowel and sing on it. This is particularly true when singing very high pitches.

VOICE BREAKS (FLIPS)

Almost every untrained singer experiences the embarrassment of voice breaks. These cracks, flips, or interruptions of a smooth vocal line often occur in the area of the first bridge or primo passaggio, the area in which the singer is transitioning from the lower register to the upper register.

A break indicates imbalances in both resonance and muscle activity.

Here’s how the flip, crack, or break happens:

When pitch ascends, if the F1/H2 coupling is continued higher than the first bridge (this is called tracking the harmonic), and the vocal folds are held static in the short/thick mode due to TA contraction, excessive air pressure must be applied in order to raise the pitch.

However, the CT muscles are also contracted, attempting to elongate the folds to raise the pitch. Eventually, the CT muscles prevail, and the TA muscles let go abruptly, so the larger part of the folds are no longer in vibration, the vocal folds suddenly elongate and abduct (come apart), and the tuning abruptly shifts from a powerful (but strained) yell-like quality (F1/H2) to a weak, breathy falsetto (F1/H1 with little energy in the harmonics). This is known as a flip.

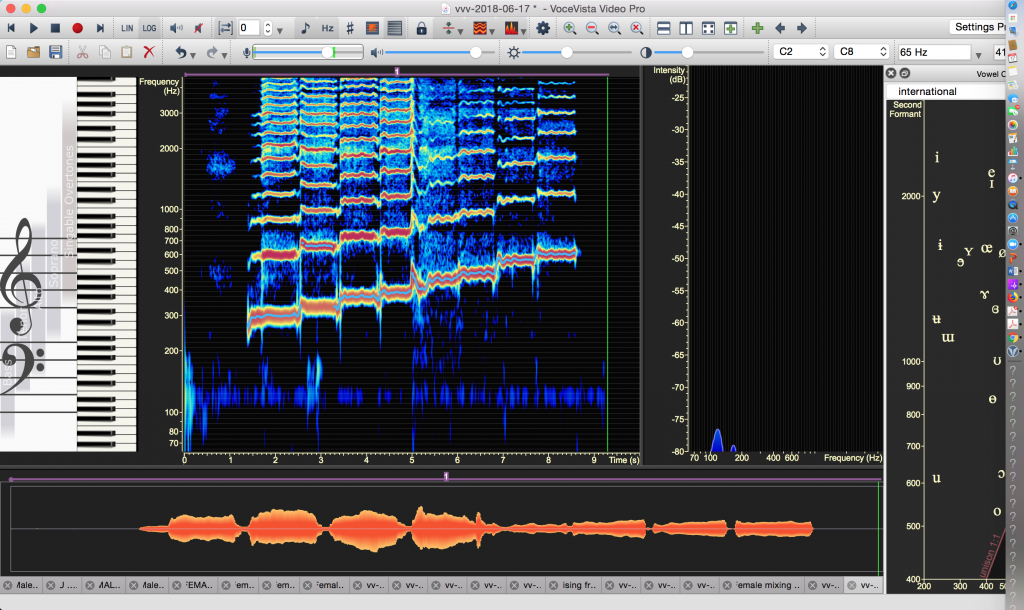

In the image below, the band of energy with the blue line is the rising pitch. The bands of energy above the pitch, or fundamental, are higher harmonics. You can see how weak they become after the primo passaggio (first bridge).

The Flip or Voice Break

Following a flip, or break, vocal production is breathy, weak, and anemic. The vocal folds are abducted, or apart. Closed quotient is very low. The singer has just experienced an embarrassing flip, or yodel, as the powerful F1/H2 yell timbre abruptly changes to a whoop- F1/H1.

A flip can be produced by by:

- Pushing chest voice upward beyond the healthy transitional area of the first bridge.

- Carrying the open vowel too high instead of modifying it to transition effectively through the bridge.

- Opening the mouth too wide, grimacing with the lips, and raising the larynx, all in an effort to track F1 too high.

- Increasing air pressure excessively in an effort to raise the pitch.

- Increasing vocal fold tension with the contraction of the TA muscles rather than allowing the lengthening and thinning process that occurs when the CT muscles tilt the thyroid cartilage forward.

- Ineffective resonance strategy due to poor vowel choice.

If you would like to learn more about your voice AND learn to sing from home for less than you probably spend for lattes every month, check out our amazing YOU can Sing Like a Star online subscription courses for singers and voice teachers.

You can learn to sing with a self-study method- IF it's the right method. The ONLY method that can take you from beginner to professional is the YOU can Sing Like a Star online subscription course with over 600 recorded exercises.

This is the best method available and the ONLY method that takes you all the way from beginner to professional singer- for far less than the cost of in-person voice lessons!

Check this amazing course out at YOU can Sing Like a Star online subscription course.

If you are a voice teacher who wants to up your game, check out the YOU can be a Successful Voice Teacher online subscription course

With over 600 recorded exercises, including Riffs and Runs- Style, you don't need to be a great pianist or vocal stylist to be a great teacher!